TBW - Survey of DeFi protocol income redistribution systems

The important question in 2026 is no longer whether a DeFi protocol generates revenue: many do, and sometimes at levels comparable to those of a world-scale fintech.

The real question is now stricter: who captures this value, who sends it back to the token, and with what degree of credibility over time?

Over the year 2025, the analysis company 1KX has estimated that users will pay a total of $20 billion in onchain fees, with almost 69% of this concentrated in just 20 or so protocols.

What we need to understand is that value is shifting from the core blockchains (Ethereum, Solana, etc.) to the applications on which they are developed: perpetual derivatives, trading aggregators, specialist DEXs or ve-token models now capture the bulk of DeFi P&L.

The problem now increasingly resembles that of private equity or infrastructure: identifying recurring flows, assessing their resilience, and above all understanding how they convert (or not) into returns for token holders.

In this context, buybacks and burns have become the common language between protocols and investors.

A buyback corresponds to the use of revenues (or part of the cash flow) to buy back tokens on the market, often in a programmatic way, sometimes followed by a burn.

A burn permanently reduces the supply in circulation.

Together, these two tools transform volatile revenues into regular buying pressure and, in some cases, a lasting contraction in supply.

But while protocols that buy back their tokens with their revenues seem, theoretically, to have found the magic formula, we will see that this metric alone is not enough.

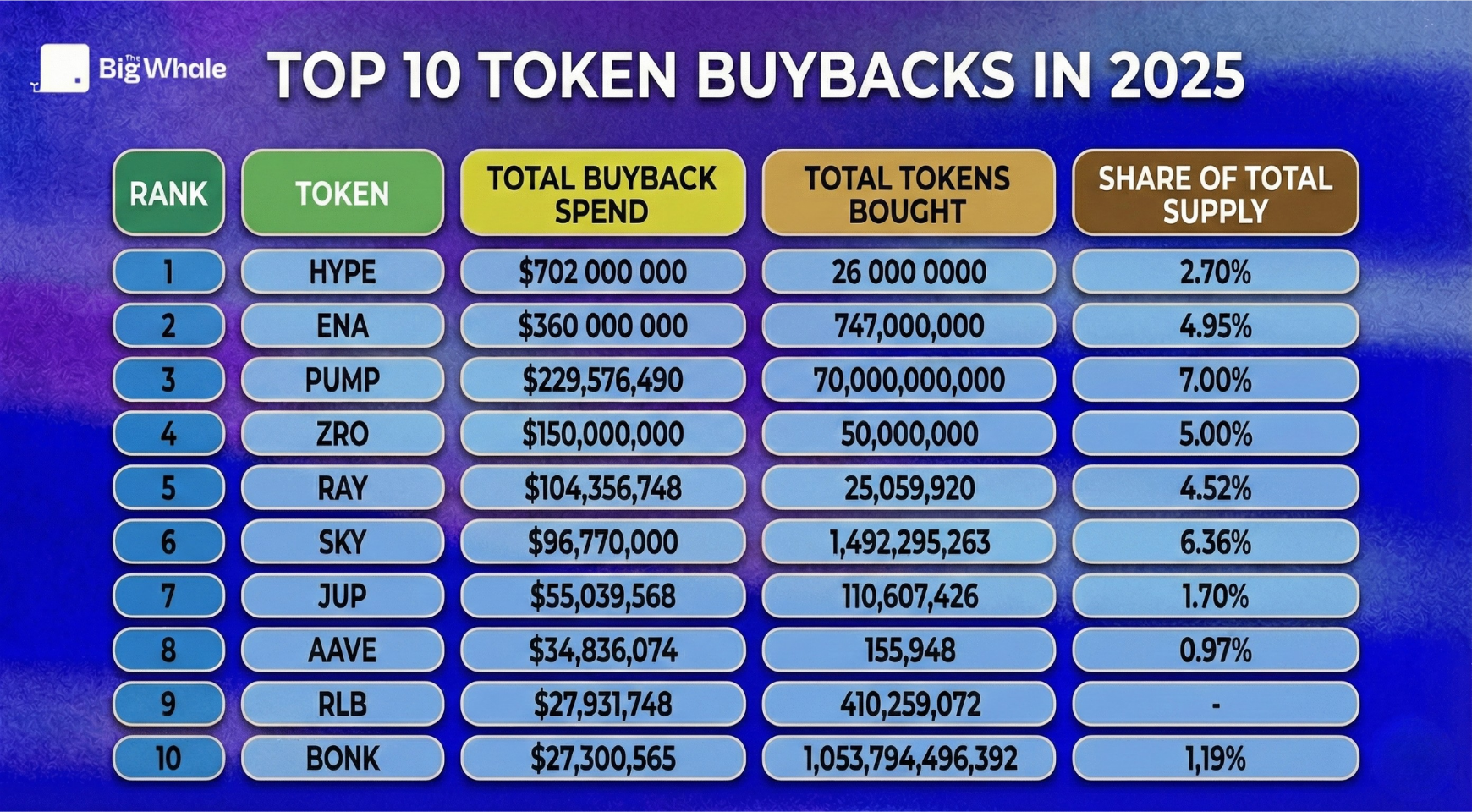

Hyperliquid and Pump.fun: the school of offensive buybacks

Hyperliquid is today the most successful example of a protocol that aligns virtually its entire economic structure with the buyback of its HYPE token.

Until August, the derivatives platform directed 97% of trading fees to an assistance fund responsible for programmatically redeeming HYPE (now 99%).

This mechanism has absorbed more than $700 million in liquidity in 2025, putting Hyperliquid at the top of the industry.

Hyperliquid thus brings the HYPE token closer to a quasi "fixed income" asset indexed to trading volumes: as long as derivatives generate fees, the protocol mechanically recycles these flows into redemptions.

But the HYPE case is a reminder that an aggressive buyback alone is not enough to create a sustainable valuation: since November 2025, the vesting of the development team has been completed and the supply in circulation will increase every month until 2027 (at a rate of $270 million per month at the current price).

The key metric is therefore not gross volume bought back, but net burn-to-mint: how many tokens are effectively removed from the free float once all sources of dilution are factored in.

In this logic, Hyperliquid seems to be following the right path, as a governance vote in December 2025 chose to destroy all HYPE tokens bought back by the assistance fund, i.e. 13% of the outstanding offering.

The project thus offers one of the best alignments to date between the value generated by the protocol and its token. Nevertheless, this has not prevented its token from recording a fall of more than 50% since its all-time high in October ($59), which can be explained by multiple events: stress on the crypto markets, falling volumes on Hyperliquid linked to the emergence of competitors (Aster and Lighter in particular) and the end of vesting.

>> HyperEVM: a network under construction backed by an on-chain trading giant

Pump.fun, meanwhile, illustrates a similar model but on a radically different market segment: memecoin speculation via Solana. Here too, the logic of redistribution is based on reducing supply. Since the launch of its PUMP token in the summer of 2025, the platform has repurchased more than $230 million worth of tokens, a record on Solana which now exceeds Raydium in cumulative buyback volume.

The point of Pump.fun is not so much to bet on a long-term model (which remains extremely speculative and exposed to high regulatory risk) as to observe, under real conditions, how far a protocol can push the "all for buyback" logic.

>> Pump.fun: analysing the business model of the memecoins cash machine

Jupiter and LayerZero: the limit of buybacks in the face of dilution

Jupiter, the leading trading aggregator on Solana, offers a useful counterexample. In 2025, the protocol spent more than $70m on a buyback programme for its JUP token, funded by a significant proportion of the fees generated by the aggregator. Despite this effort, the price of the token has fallen by around 89% from its high, even though buybacks accounted for up to 50% of revenues.

The reason is essentially mechanical: Jupiter is facing an unlocks schedule of around $1.2 billion worth of tokens until 2026. In such a context, buybacks are unable to offset a rapidly expanding net supply.

LayerZero is in the same situation: despite a significant amount of buybacks ($150 million in 2025), the token is suffering from too much money being issued for value to be preserved (almost 60% of ZRO tokens have not yet been put into circulation).

These cases highlight a simple rule: a buyback programme, even a well-funded one, only creates value for holders if the trajectory of issuance and unlocks is controlled. Otherwise, every dollar spent on buybacks is quickly neutralised by the new supply. Hence the open debate within the governance to consider redeploying revenues towards user incentives or product development rather than buybacks.

Aave: a revenue sharing model close to traditional standards

Aave, for its part, has gradually reoriented its model to offer a more legible trajectory to AAVE token holders. After an initial phase marked by a large issuance of tokens to finance growth, in 2025 the DAO endorsed a permanent buyback programme of $50 million a year, financed directly by protocol revenues.

In practice, Aave is thus devoting a recurring budget to accumulating AAVEs on the market, extending a policy that had already begun where around $35 million had been used to buy back tokens in 2025, or nearly 1% of supply.

The difference from more aggressive models lies both in the nature of the underlying (on-chain lending, a more utilitarian but less explosive activity than derivatives or memecoins) and in the governance culture.

Aave is thus closer to a credit infrastructure with a quasi-fiscal framework: revenues are used both to strengthen the protocol (security fund, development) and to support the token via a capped but predictable redemption.

>> Fee Switch dans la DeFi : Entre-revolution-economique-et-mirage-marketing

La grille de lecture qui se dessine

The first step is to make a clear distinction between the fees paid by users and the revenue actually captured by the protocol after redistribution and costs, and then to analyse the concentration and sustainability of these flows.

The second step is to examine the token policy as one would read a bond prospectus: issuance rules, unlocks calendar, buyback mechanisms, programme horizon.

Hyperliquid and Pump.fun show that a very offensive buyback can produce a powerful effect on supply, but that this remains fragile if future issuances are massive or if regulation calls the model into question.

Jupiter or LayerZero illustrate the limits of such a scheme in the presence of strong programmed dilution, while Aave highlights more disciplined trajectories, better aligned with a logic of net value creation.

The challenge is not just to identify the protocols that generate revenues, but those that manage to transform these revenues into predictable returns, contractualised by the code and protected by credible governance.

As long as these three conditions are not met (robust economic flows, net supply under control, stability of rules) buybacks and burns will remain interesting signals, but insufficient to justify a significant long-term allocation.